Battle of Iwo Jima: Feb. 19 to March 26, 1945

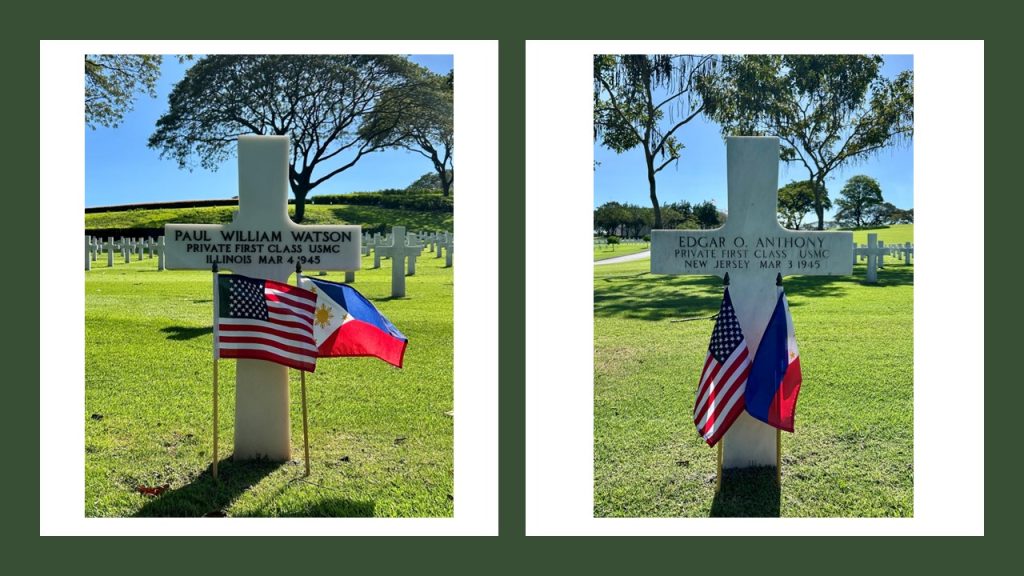

Many of the American war dead from the Central Pacific during World War II were laid to rest at the National Memorial Cemetery of the Pacific in Hawaii. However, 48 unknown service members from Iwo Jima are buried at the Manila American Cemetery in the Philippines. Two others, Pfc. Paul W. Watson and Pfc. Edgar O. Anthony, were listed as missing and later identified and buried at the cemetery. At the time, it was known as Fort McKinley U.S. Military Cemetery.

D-Day: Operation Detachment

Watson disembarked with Company B, 1st Battalion, 28th Marines, 5th Marine Division, Feb. 19, 1945, on the approximately 10 square mile island, about equidistant between Tokyo and where Americans were based in the Mariana Islands.

Operation Detachment and the capture of Iwo Jima would fulfill three goals. The U.S. wanted to curb early reporting of their air strikes to Japan. The second benefit of capturing the island was ending Japanese air raids over the Mariana Islands. Finally, and possibly most importantly, the U.S. wanted control of the island’s three airfields to provide staging for aircraft to reach the Japanese mainland and for aircraft in distress to have emergency landing capabilities in the Pacific.

While Feb. 19, 1945, is recognized as the beginning of the operation, U.S. B-24 Liberators began bombing the island 16 days prior, dropping more than 1,000 tons of bombs. Three days before D-Day, U.S. Navy battleships joined in, bombarding the island, but to little avail.

As U.S. troops – including the largest force of Marines deployed in a single battle – discovered, the Japanese forces were entrenched on the island in more than 1,500 bunkers, some more than 75 feet deep into the mountains, along almost 16 miles of tunnels. The previous weeks’ bombings had in some cases created more cover for the almost 21,000 Japanese troops hidden on the island.

As troops and vehicles disembarked, the island’s black volcanic sand slowed their movement on the beaches. According to an article from the National WWII museum, “one Marine described it is as ‘trying to run in loose coffee grounds.’”

While slowed, the Marines were not deterred and by later that morning had isolated Mount Suribachi, cutting it off in the south at the island’s narrowest point.

D-Day plus 4: An iconic moment

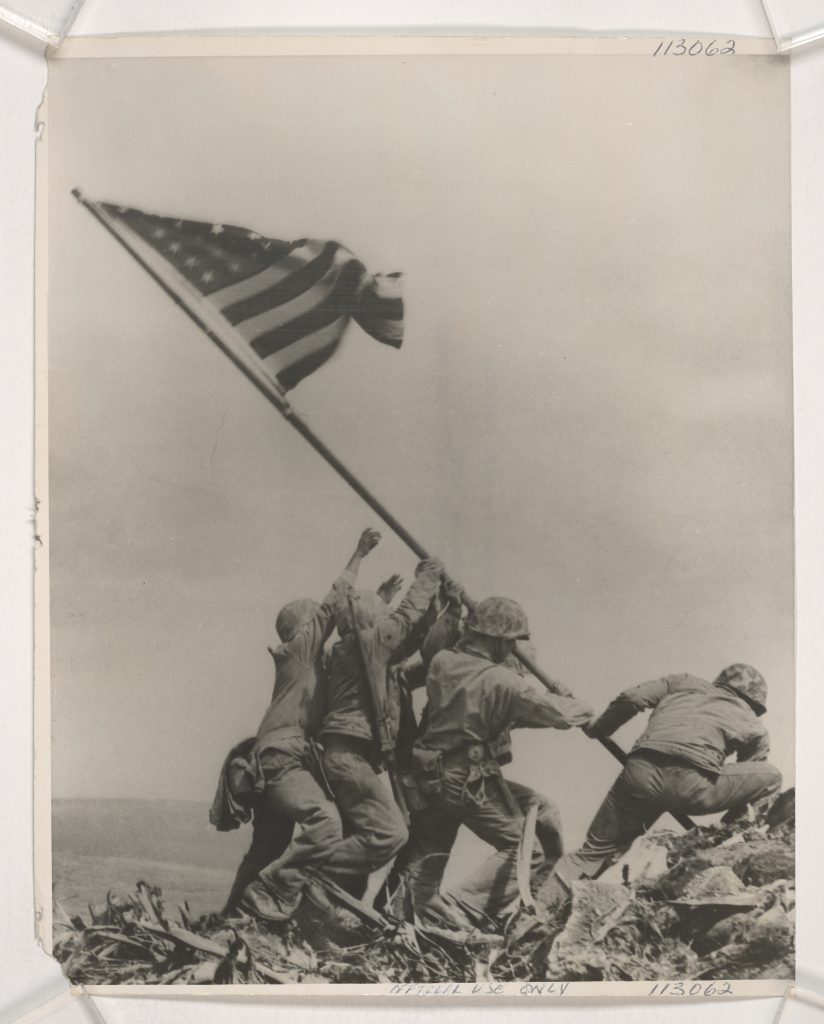

While the Marines cut Mount Suribachi off from the rest of the island Feb. 19, it wasn’t until four days later they planted the U.S. flag at the summit in an action recognized by many thanks to Associated Press photographer Joe Rosenthal.

A smaller flag had originally been placed at the summit, but as a group of Marines hoisted a second, larger flag, Rosenthal captured the photo that became the inspiration for the Marine Corps War Memorial in Arlington, Virginia. The statue was carved by Felix W. de Weldon, who also carved the Marine Monument at Belleau Wood, a tribute to another well-known Marine action.

D-Day plus 13: Their final day

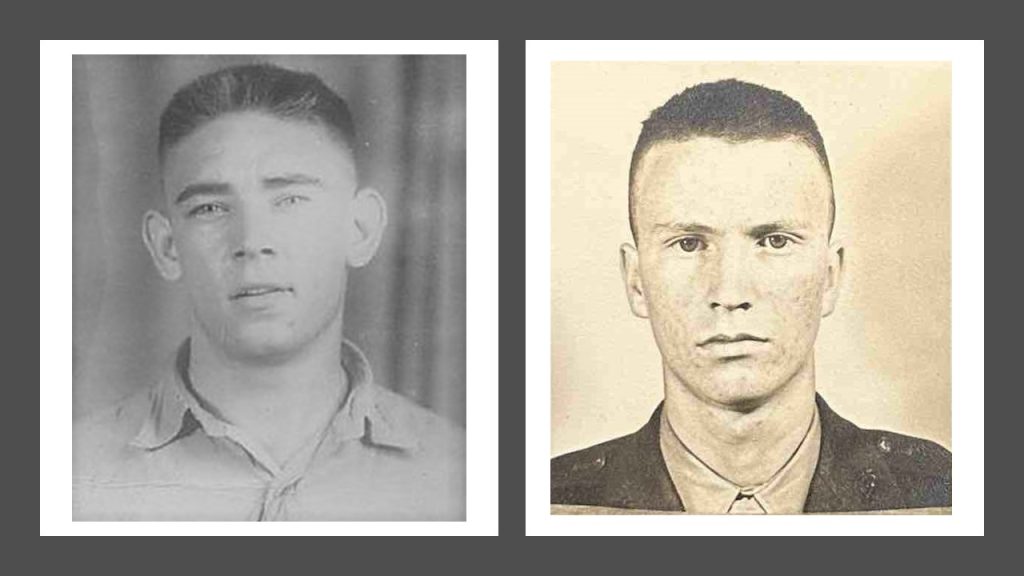

At 4 p.m. March 3, 1945, Watson, a native of Bloomington, Illinois, was last seen as his platoon advanced to assault a Japanese pillbox on the north side of Hill 362. His unit withdrew due to heavy enemy fire, but 19-year-old Watson was missing. Watson’s body was not recovered initially but later identified as an unknown interred in the 4th Marine Division Cemetery.

The same day, Anthony, of Company I, 3rd Battalion, 26th Marines, 5th Marine Division, and a native of Wortendyke, New Jersey, was killed when a sniper struck the flame-thrower he was carrying. Anthony would have turned 23 in April. Initially listed as missing in action and non-recoverable, his remains were later identified.

An ‘unselfish contribution toward a better world’

Almost 80,000 Marines, 450 Naval ships and several thousand Navy Seabees participated in the Battle of Iwo Jima. Watson and Anthony were just two of the almost 7,000 American service members killed. Nearly 20,000 were wounded. The battle remains the most highly decorated single engagement in U.S. history with 22 Marines and five sailors receiving the Medal of Honor.

In a 1946 letter, officially informing Watson’s father his status had been changed from missing to deceased, U.S. Marine Lt. Col. D. Routh, wrote, “I realize that there is nothing I can say to comfort you, but I hope you will find consolation and pride in the fact that your son did his part in helping to bring this war to a successful conclusion, and that the knowledge of his patriotism and unselfish contribution toward a better world in the future will sustain you in your grief.”

Those who fought to secure Iwo Jima brought the Allies one step closer to victory in the Pacific. In the coming months, after the end of the battle March 26, 1945, more than 2,200 American B-29s used the Iwo Jima airfields for emergency landings, saving the lives of more than 24,000 airmen. Over 4,200 other smaller aircraft were flown from the island against Japan, and air-sea rescue teams operated from the island to rescue downed air crews in the Pacific.

The search goes on

In 1950, both Watson’s and Anthony’s families received letters notifying them that their sons had been identified. The Defense POW/MIA Accounting Agency is tracking more than 600 missing service members related to the Battle of Iwo Jima. The agency continues to work with the American Battle Monuments Commission to identify unknown service members buried at ABMC sites, including the 48 unknown service members at Manila American Cemetery.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.