By Johnny Matherne

Rhone American Cemetery Superintendent

Jumping out of a plane is not normal, and when in the military service, it is not required. Airborne units are made up of volunteers. Those who become paratroopers create close, special bonds with their brethren. Imagine how devastating it must have been for a paratrooper of the 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion to enter the war with over 700 of his comrades, but at the war’s end, just over 100 of them are left. None of his close buddies are alive and his well-respected commander is dead. To make matters worse, the short but incredibly important history, contributions, and sacrifices of his unit are almost forgotten (and maybe even deliberately erased) from the history books.

So, what happened?

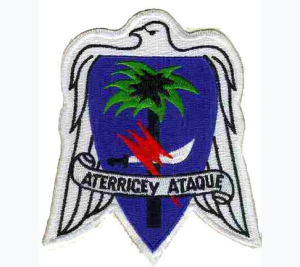

The 551st was formed at Fort Kobbe Panama Canal Zone on Nov. 26, 1942 [1]. The favorite expression of their commander, Lt. Col. Wood Joerg, was, “Get off your ass!”, and the nickname “GOYAs” was born. The battalion prepped for a surprise attack on the Vichy French island of Martinique but the French commander surrendered [2], and the GOYAs were sent stateside to Camp Mackall, North Carolina.

At its inception, the 551st was made up of a rowdy lot of mavericks. Its early, restless days in Panama and at Camp Mackall were marked by high rates of AWOL, fist fights, and venereal disease. Matters were further exacerbated when their respected commander, Joerg, was put in command of another battalion. His replacement was his polar opposite in age and personality, Lt. Col. Rupert Graves. The rates of AWOL only increased, and for unspecified reasons, Joerg was eventually put back in command. Exasperated at the state of his battalion, he addressed the jailed AWOL paratroopers. If they swore to him that they’d get back in line, he’d get them out of jail. They swore to him, and he kept his word. They were released – just in time to head overseas [3].

The GOYAs were sent to Italy but did not see combat there. Instead, they received a new mission: invade Southern France as a part of Operation Dragoon. They were organized as part of the 1st Airborne Task Force and would participate in the first daytime jump of the war, jumping near Nice, with some scattering miles away to the town of La Motte. They were also the first unit to reach and liberate Draguignan on Aug. 16. Later, they scored yet another first. In Draguignan, four paratroopers kicked in the door of a building where a Nazi flag flew. Inside, they came face-to-face with the district commander of the occupied town, Maj. Gen. Ludwig Bieringer. The 551st could now boast they were the first American unit to capture a German general in the European theater [4].

After Draguignan, the GOYAs were sent to patrol the snowy Franco-Italian border. They saw light combat in the Alps with low casualties. They turned in their skis in November, boarded trains, and departed for northeastern France. In December, the existence of the 551st would be forever altered by one of the most famous battles of the war.

The Battle of the Bulge

On Dec. 16, 1944, Hitler launched a last-ditch effort to win the war. This surprise offensive campaign on the Western Front caught the Allies completely off-guard, and it would come to be known as the Battle of the Bulge.

For the 551st, the Battle of the Bulge was a nightmare. With just under 700 men [5], they started with little to no winter gear and little to no artillery support. They were chosen to conduct raids in which they were outnumbered. Little by little, the GOYAs numbers were reduced. They would receive their biggest blow at a Belgian town called Rochelinval.

By Jan. 3, the Germans were well dug in at Rochelinval. Between Jan. 3 and 7, the 551st fought with little artillery support, which became zero artillery support after all of their forward observers had been killed. They also conducted a bayonet charge, which was one of the very few during World War II. Casualties mounted. Company A of the 551st started the fight on the Jan. 3 with 150 paratroopers. By nightfall, only 50 men remained. Later, some men would try to find sleep when they could, never waking as they froze to death during the night.

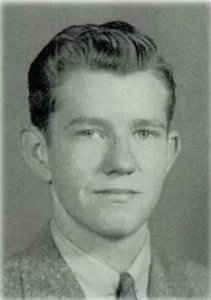

On Jan. 6, Joerg was ordered to attack Rochelinval. He balked, as his men had not eaten in three days. No food came, and on the 7th, the fate of the 551st was secured. They attacked Rochelinval. Joerg was killed by an artillery round, shrapnel piercing his helmet. By nightfall, all that remained of the battalion was just over 100 men. The 551st had been decimated, and still somehow took the village.

Long overdue recognition

Instead of receiving accolades and awards, the 551st was disbanded, and many of their paratroopers were absorbed into the 82nd Airborne Division. From their inception until the end, the unit received very little recognition. Their records were either lost or destroyed. It wasn’t until Feb. 23, 2001, through the efforts of U.S. Congresswoman Constance Morella, surviving members of the 551st, and Gregory Orfalea, son of a GOYA and author of a book about the 551st, that the GOYAs were finally recognized with a Presidential Unit Citation for their role in World War II. General Eric Shinseki awarded the citation and recognized the 551st for participation in five campaigns [6].

It has been said, including by our own Commissioner Michael Smith, that someone can lose their life twice: the first time is when they die, and the second time is when they are forgotten. As long the American Battle Monuments Commission exists, the men of the 551st who are buried at Rhone American Cemetery and elsewhere, along with all service members and civilians resting in our cemeteries, will not die a second time.

[1] Shelby L. Stanton, World War II Order of Battle: An Encyclopedic Reference to U.S. Army Ground Forces from Battalion through Division 1939-1946 (Stackpole Books, Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania, 1984), page 266.

[2] Gregory Orfalea, Messengers of the Lost Battalion: The Heroic 551st and the Turning of the Tide at the Battle of the Bulge (The Free Press (Simon and Schuster) New York, NY, 1997), 66.

[3] Gregory Orfalea, The Lost Battalion of the Ardennes (The Antioch Review, Spring, 1994, Volume 52, Number 2, War), 257.

[4] William B. Breuer, Operation Dragoon: The Allied Invasion of Southern France (Presidio Press, California, 1987), 226.

[5] Orfalea, The Lost Battalion of the Ardennes, 265. Accounts on unit strength vary, but the literature shows that the unit started with somewhere around 800 men. At the Battle of the Bulge, it was around 700, and before the unit was deactivated, they were left with just above 100.

[6] Official ceremony awarding the Presidential Unit Citation, given by General Eric Shinseki at the Pentagon, 2001. Part 1 – 551st Parachute Infantry Battalion – Presidential Unit Citation – Part 1 (youtube.com)

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.