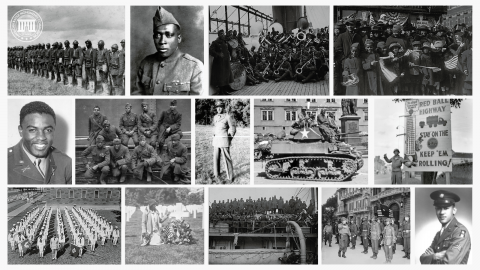

African Americans have served honorably in American wars dating back to the American Revolution. The American Battle Monuments Commission remembers and honors their sacrifice.

In World War I, racial prejudice restricted most African American soldiers to labor and service positions, but two segregated divisions of combat troops, the 92nd and 93rd, were raised during the war. These included pre-war African American National Guard units such as the famed 15th New York/369th Infantry, the “Harlem Hellfighters” and the 8th Illinois/370th Infantry as well as additional regiments of draftees and volunteers. One of these soldiers, Cpl. Freddie Stowers, was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor in 1991 for leading his squad in a successful assault on an enemy strongpoint despite his own mortal wounds.

World War II again saw African Americans answer their nation’s call. Many served in support positions, including the famed Red Ball Express that fueled the Normandy breakout and advance across France. Others served in combat units, including the 92nd Infantry Division that fought in the Italian theater. World War II also saw the first African American aviation units, with the “Tuskegee Airmen” of the 332nd Fighter Group flying 1,578 combat sorties, earning three Distinguished Unit Citations and 96 Distinguished Flying Crosses. The Army also formed a number of segregated Tank and Tank Destroyer Battalions; Staff Sgt. Ruben Rivers of the 761st Tank Battalion earned a Silver Star and the Medal of Honor for his conspicuous gallantry and combat leadership.

African American women served in World War II as well, as part of the Women’s Army Corps. The 6888th Central Postal Directory served in the United Kingdom and France. Facing a backlog of mail, the “Six Triple Eight,” worked in three shifts around the clock and processed some 65,000 pieces of mail per shift. Three members of the 6888th tragically lost their lives in a jeep accident, and are buried at Normandy American Cemetery.

While the World War II U.S. military followed a strict policy of segregation, near the end of the war this broke down in the face of the heavy casualties, and African American volunteers, many from support units, were sent as infantry replacements to all-white units. One of these soldiers, Pfc. Willy F. James of the 104th Infantry Division, earned the Distinguished Service Cross for his valor in observing the enemy and leading a squad in an assault, including sacrificing himself in an attempt to rescue his fatally wounded platoon leader. In 1997, James along with six other African Americans, was awarded the Medal of Honor following a review of racial discrimination in the processing of America’s highest award during World War II.

African Americans also served with incredible bravery in the Pacific Theater from the very first day of the war. U.S. Navy Cook 3rd Class Doris “Dorie” Miller was serving aboard the USS West Virginia in Pearl Harbor on the morning of December 7, 1941. As his ship came under attack from Japanese aircraft, Miller helped several wounded sailors before manning an anti-aircraft gun and shooting down several Japanese planes. For his bravery, Miller was awarded the Navy Cross. In 1943, Miller was serving on the USS Liscome Bay when it was sunk by a Japanese submarine. Miller’s remains were never recovered, and he is honored along with 18,094 other Missing in Action (MIA) from World War II on ABMC’s Honolulu Memorial, not far from where he earned the Navy Cross on December 7th.

The segregated 93rd Infantry Division, nicknamed “the Blue Helmets” in honor of its service with the French Army in World War I, also served in the Pacific in World War II. The division served on Guadalcanal and New Guinea, where it accepted the surrender of 41,000 Japanese at the end of the war. Over 40 members of the 93rd are buried at Manila American Cemetery.

Following President Truman’s Executive Order 9981 in 1948, the Korean War was the first American war to see the wide-spread existence of integrated units, although segregation did not end completely until the 1953 dissolution of the last all-black unit. African Americans again served with bravery and honor, now shoulder to shoulder with their white comrades. This continued in the Vietnam War, which saw the highest proportion of African Americans ever to serve in an American war. In 1965, almost 25% of those Killed in Action were African American.

The 8,209 MIA of the Korean War, and the 2,504 of the Vietnam War, many of them African American, are honored on ABMC’s Honolulu Memorial.

Commissioner Raymond D. Kemp Jr. actively supported this remembrance by recording these videos that have been accepted to run on AFN Europe and AFN Pacific.

Every day, throughout the world, the American Battle Monuments Commission works to ensure that their dedication, bravery and sacrifice are not forgotten.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.

An official website of the United States government. Here's how you know.