5 things you may not know about Epinal American Cemetery

Epinal American Cemetery is located on a plateau above the Moselle River in the Vosges Mountains near Epinal, France. This World War II American Battle Monuments Commission site contains the graves of approximately 5,300 service members. More than 400 names are also commemorated on its walls of the missing.

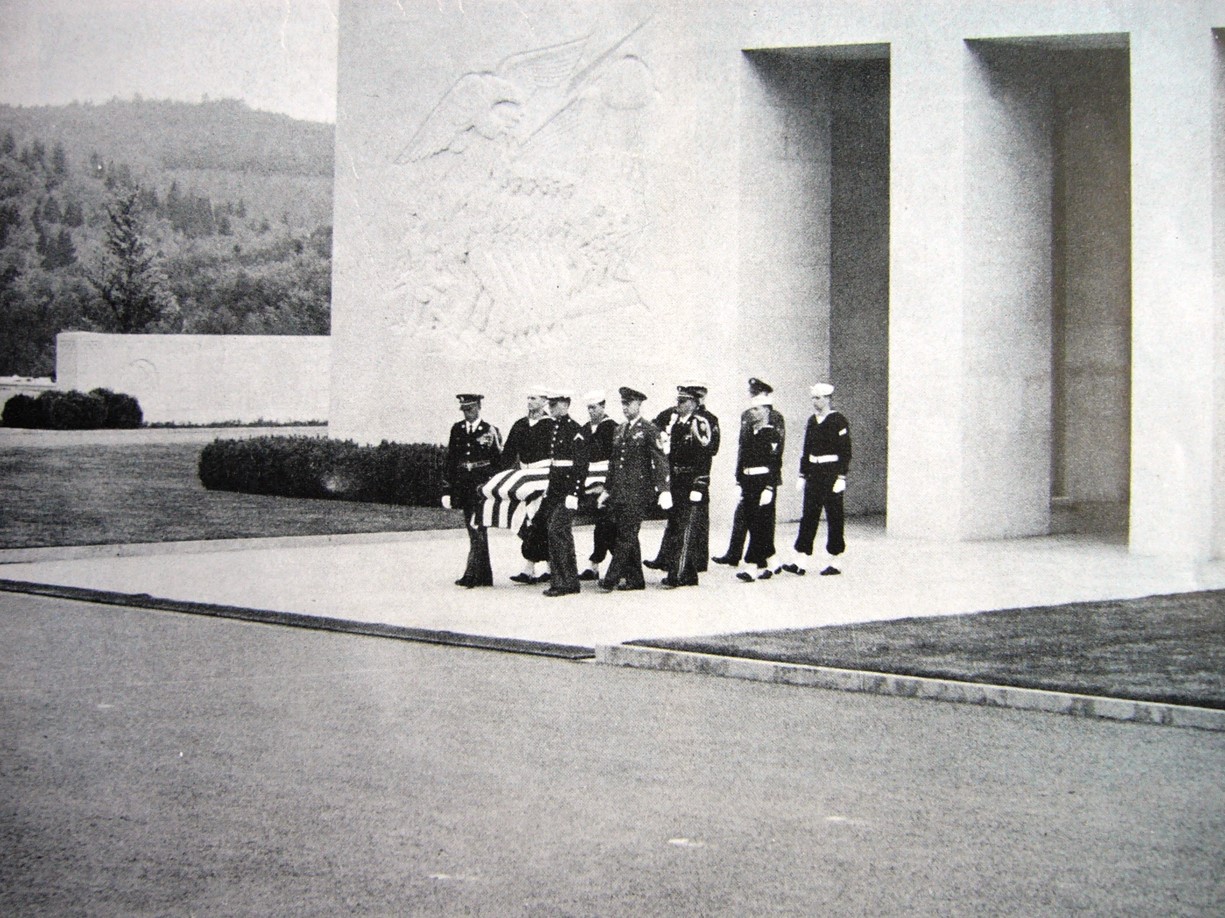

Unknown service member selected for Arlington tomb

The Tomb of the Unknown Soldier at Arlington National Cemetery is the final resting place for the remains of unknown service members from World War I, World War II and the Korean War. One set of remains was included from each war, including the Vietnam War, but that service member was later identified and disinterred.

In 1958, the unknown service member from the European Theater of Operations for World War II was selected at Epinal American Cemetery from 13 unknowns – drawn from across the European Theater of Operations. This unknown was transported to the U.S. aboard a U.S. Navy destroyer, and united with the selected WWII unknown from the Pacific Theater of Operations.

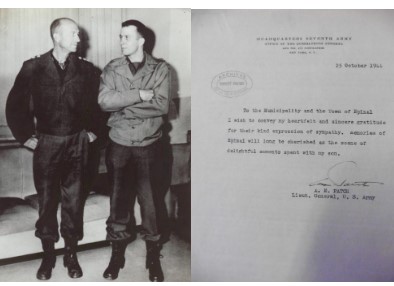

The Commanding General’s Son:

Capt. Alexander M. Patch III, son of Seventh Army commander, Lt. Gen. Alexander “Sandy” Patch Jr., is buried at Epinal American Cemetery. Patch was killed in action Oct. 22, 1944, while commanding Company C, 315th Infantry Regiment, 79th Infantry Division.

Attacking fortified German positions near Lunéville, France, Patch led from the front, encouraging his men to keep fighting until he was wounded in the shoulder. Without wavering, he continued to lead the attack for two hours, bleeding profusely and weakening from blood loss. Patch refused treatment until his soldiers had achieved their objective.

His decorations include the Distinguished Service Cross, Silver Star and three Purple Hearts.

“Go For Broke:” The motto of the 442nd Regimental Combat Team

Epinal American Cemetery contains the graves of 12 Japanese American soldiers (Nisei), with one listed on the Walls of the Missing, who served with the 442nd Regimental Combat Team. The 442nd RCT was responsible for liberating the towns of Bruyères and Biffontaine, and for the rescue of the “Lost Battalion” of the 141st Infantry Regiment, 36th Infantry Division.

The 442nd RCT faced prejudice at home and overwhelming odds on the battlefields of France and Italy in some of the most intense fighting of World War II. They made “Go For Broke” an appropriate motto. In just 19 months of combat, the 442nd RCT was honored with seven Distinguished Unit Citations, more than 4,000 Purple Hearts, and a large number of individual decorations for bravery including 21 Medals of Honor, 29 Distinguished Service Crosses, 558 Silver Stars, and more than 4,000 Bronze Stars. They remain to this day the most highly decorated unit in U.S. history.

They led the Way

In World War II, U.S. Army Air Forces Bombardment Groups were designated typically into four types: Light (L), Medium (M), Heavy (H), and Very Heavy (VH). So what, precisely, is a Bomb Group (P)? (P) designated “Pathfinders” – specialized heavy bombers outfitted with a top-secret air-to-ground radar system. This unit, dubbed the “Mickey,” allowed for precision bombing missions in zero visibility, day or night. “Mickey” radar-equipped B-17s and B-24s would lead the bomber formations, directing the other aircraft to release their payload on target. Pathfinder missions and the techniques developed by these intrepid crews proved the feasibility of aircraft radar in a combat environment.

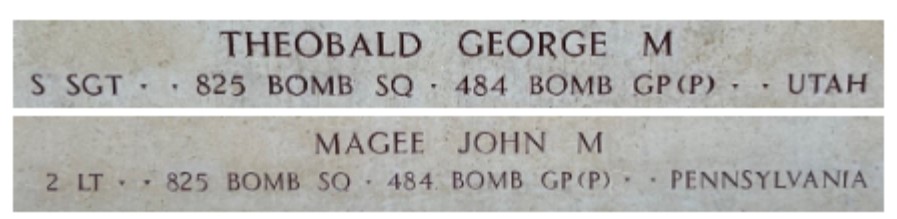

Two members of the 825th Bomb Squadron, 484th Bombardment Group, are found on the Walls of the Missing at Epinal American Cemetery.

One of them is Staff Sgt. George M. Theobald, who died during a mission over Munich, Germany, on June 13, 1944. Theobald was part of a B-24 crew shot down near its target.

The second one is 2nd Lt. John M. Magee. On June 16, 1944, Magee was temporarily assigned to fly with a B-24 crew of the 756th Bomb Squadron, 459th Bomb Group in a bombing mission against the Nova Schwechat oil refinery in Vienna, Austria. He died when the plane caught fire, and he was unable to exit.

A Unique Battle Map

The battle map of Epinal American Cemetery is unique in that it depicts the battles of the Vosges, and also operations throughout Eastern France and Germany in 1944 and 1945. Starting with the landings of Operation Dragoon on Aug. 15, 1944, it traces the path of U.S. Seventh Army and First French Army forces up the Rhone River valley, the meeting with U.S. Third Army forces moving from Normandy, the liberation of Epinal on Sept. 24, 1944, and continuing operations across the Rhine in mid-1945.

Created by artist Eugene Savage in 1952, the glass mosaic was initially assembled in the U.S., then cut into sections and shipped to Epinal American Cemetery and installed in the map room.

It was restored in 2021 as the mosaic showing some signs of general wear. On top and before these restoration procedures took place, the entire mosaic was professionally cleaned. This was done by spraying a latex substance all over the mosaic. After this latex solidified, it was gently peeled off, removing the dust and grease that had settled on the mosaic over the years. Then, there was a prioritization in the restoration procedures. Once all the restoration work was executed a microcrystalline wax was applied on the surface and the mosaic tiles were polished using a dry cloth. This last process gave the overall surface of the mosaic battle map back its brilliance.

Sources:

EPAC Staff

ABMC Historical Services

ABMC documents, brochures and website.

ABMC Historical Files

Municipal Archives of Epinal

“The Unknowns of World War II and Korea,” DA PAM 870-1 / NAVPERS 15930 / AF PAM 143-1-2 / NAVMC 2510, US G.P.O. 1959

“Go For Broke,” C. Douglas Sterner, American Legacy Historical Press, 2008.

“Lost Battalions: Going for Broke in the Vosges,” Franz Steidl, Presidio Press, 1997.

“The Cross of Lorraine: A Combat History of the 79th Infantry Division,” US Army, 79th Infantry Division, Army and Navy Publishing Company, 1946.

National Archives of the United States, Missing Air Crew Reports: MACR 6321-7, 29 Aug 1945

U.S. Air Force Historical Research Agency, Maxwell AFB, AL.